Marie watched herself in the mirror, running the fine-toothed comb down through her long black hair. Keeping her movements slight and to a minimum, she watched her hands, one with its light grip on the comb and the other open flat and hovering behind each tuft the comb ran through, move in a way that reminded her of the stiff, statuesque movements of a doll’s unarticulated limbs. With her head tilted to the side, her hair cascading down over her left shoulder, she admired her bared neck, her right sternocleidomastoid muscle taut.

Her reflection in the mirror became her self in front of others, and she thought about how beautiful her neck would look in that soft light that reigned throughout all the parties she went to, how it would expose itself, long and slender and irresistible, when she would slowly, with controlled movements, bend down to fix her dress, or, if she was sitting in a chair, to pick up something she’d covertly, expertly dropped to the ground, all the while feigning a calm surprise — eyebrows slightly raised, lips parted as if exhaling some painful pleasure — at her clumsiness.

Slowly. Of course she would bend slowly — all her movements would be restrained and performed in a graceful and conscientious way, a measured way, without panic. Because only without panic would the movement be beautiful; beautiful in the way her hands looked now as she fastened one earring and then the other through her earlobes, with the fingers unnecessary for the process unmoving and the ones that were necessary also unmoving — they were merely petrified props softly holding up the earring and the fastener, while her wrists did all the work. Marie would be loath to allow herself frantic movements: movements without the backing of her knowing, her awareness, a backing she sometimes had to pretend.

This way, moving but not really moving, she could guarantee to herself that she would look to others as she looked to herself in the mirror when she sat poised and posed in front of it, when she looked to herself her most beautiful. Like a painting. This way, even when she accomplished a movement, she could look like a painting.

It wasn’t tiresome looking this way at parties. In fact, Marie quite enjoyed it — posing could be fun, and the thought that others saw how beautiful she looked was tremendously pleasing to her. The tiresome aspect was rather the social aspect of parties such as the one for which she was readying herself now: the party at Katrina Ivan’s newly renovated house.

Marie wound up her favourite lipstick, a beige pink, and admired for a moment the unique, completely idiosyncratic sculpture carved out by her daily use. She felt it incumbent upon herself to admire the sculpture before every use, because it changed after every use, was always in flux. She then stretched out her lips and began to apply it, changing the shape of the sculpture yet again as if she were an indecisive perfectionist striving for the representation of gods.

Marie got invited. Of course Marie got invited to all the events — how could she not? Being as beautiful as she was, it would be criminal not to invite her. She sighed a languorous smile into her lips and lightly kissed some rouge onto her cheeks with a sponge, enough so as to make them ethereally glow, but not so much as to make them seem artificially emblazoned, or even bulkily lacquered the way she had seen being sported by some of her co-partygoers.

And she knew for a fact that it was her beauty that got her invited to all the parties: she had once overheard Fiona Charleston, of the Charleston Department stores, say Marie was invited quite simply as window dressing. Marie was not too much fazed when she heard this, for she had suspected this sentiment in her hostesses all along. She knew she was no good at talking to people, and for this reason she often found the parties exhausting.

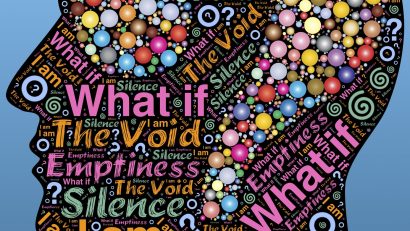

Her problem was that she thought too much — thought too much before she spoke, thought too much about what the right thing to say would be to a particular person, delayed too long and forced the silence to stretch uncomfortably. And as the silence stretched, and then as she began saying the wrong thing to the wrong person — something interesting she had read but that was apparently of no interest to anyone at any of the parties she went to; facts about animals, philosophical theories, why the movement of the clouds this year was especially different — she observed in the other the signs, of the genre of slightness that she had become an expert at performing and reading. With their own slight movements her listener’s face out of disinterest dropped: the muscles around their eyes slackened, their ears drooped, their mouth pulled down at the corners, and, most importantly, their eyes began to wander, looking for something better — because though beauty was apparently poignant enough to initially lure an interlocutor, it was not enough to keep them.

And so it was that Marie sighed once more as she began to apply her mascara. Would it that she could send her own picture along — better yet, would it that she could send her reflection along, for then at least greater movement would be possible, movement amongst the guests. She could this way serve her function as window dressing and mime social etiquette. Plus, she liked the way she was in her reflection, her features reversed. More symmetrical this way, thought Marie. Would that her reflection go to the party, to all the parties, and leave her here in her apartment alone, where she would not bore anyone, where she needn’t stress about talking to others.

What was more was that she was tired — dead tired and was having a tough time suppressing her yawns. She had only the previous day moved into her new apartment and hadn’t had any sleep between that evening, unpacking, and this one on which she sat applying her makeup. And added to yesterday was this morning spent with her new students, the Benson twins — a boy and a girl about to enter the second grade and whose mother, Mrs. Benson, wanted them to master third-grade math before September, but who refused to learn anything as it was July and July is summer vacation, they said in unison, completely ignoring Marie sat in front of them surrounded by their open workbooks.

Marie sighed again. She was ready. With a half-hour to spare. A yawn trembled through her body and she decided she could squeeze in a nap before leaving for her sentinel duty. Were she not so tired she would, as usual, just sit in front of her mirror, practicing moving without moving — this was something she enjoyed doing no end, something she would often spend hours and hours doing. Just watching her reflection. But she couldn’t, not today.

She got up from her vanity table and sat down on her bed, resting herself carefully against and amongst her pillows, so as not to mess her hair or ruffle her dress. Comfortable but still poised enough that she wasn’t ruining her look, she closed her eyes, unaware that she had neglected her reflection in the mirror.

Marie’s reflection still sat, sat still, all dressed up as she was, in the mirror at her vanity table.

***

What woke Marie was the ringing of her cellphone. She scrambled about in her bed in the darkness, trying to find it amongst the folds of her dress.

She got to it just as its ring was dying out. “Hello?” she mumbled, her voice guttural.

“Hi Marie,” shouted Katrina’s voice, competing to be heard over explosive traffic sounds. “I’m calling like you asked me to — to remind you to bring over the beer and wine tonight.”

“What?” Marie sat up in bed, her mind rolling and churning in her head like a doomed schooner in a storm. She looked around — shafts of golden light shimmering with dust speared in through the gaps in the thick curtains she needed for her migraines, making the curtains themselves seem to have gilded edges. “Why am I bringing wine?”

“You said you would last night!”

“Last night?”

“Listen, I can’t talk right now, I’m running late for a lunch meeting — just remember the drinks, okay? And remember to come back before the other guests arrive. Don’t be late like last night!”

Katrina laughed and hung up before she could hear Marie ask confoundedly: “What are you talking about?”

I was late last night? Marie combed through her memories but could not remember being at Katrina’s. Couldn’t remember promising to bring wine tonight, could not even remember being invited to anything anyplace tonight. Lunch meeting. She looked down at her phone: 12:06 pm. The Bensons! A voice in her head screamed, and she scrambled and tumbled out the door, grabbing her satchel on the way. She’d already missed her lessons — they were scheduled to last from 10 am to 11 am, and there was now no point in the rush. But Marie didn’t think of this — she thought only of Mrs. Benson’s rule of punctuality, incompliance with which, she’d insinuated, would lead immediately to termination of employment. Just get to the Bensons’, said the voice in her head again and again.

Marie ran as fast as she could to the little townhouse, and the distance that might take her fifteen minutes to close by bus was now traversed in under ten minutes on her hurrying feet. She arrived dripping with sweat at the Bensons’ door.

“You’re back already?” Mrs. Benson asked as she opened the door.

Marie had to take a moment to catch her breath before she was able to speak, and when she was, all she could muster was a bemused, “What?”

“Did you forget something?” Mrs. Benson asked, looking around behind her, as if in leaving the townhouse Marie had dropped a scarf. But Marie hadn’t left, she had just arrived.

The Benson twins came running up in a cloud of giggles, and both in unison called Marie’s name with absolute, unadulterated glee, which only served to confuse Marie further. The twins had hassled and harassed her all day yesterday, playing on her probably every prank they had in their arsenal.

“Are you going to a party?” the boy asked. Marie looked down and the realization that she was still dressed from last night for Katrina’s party hit her like an arctic wind, sending a steely chill down her spine. She shuddered to think the kind of greasy and caked mess her makeup had congealed into now, after a night spent sleeping on it. Probably drooling, too.

“But why do we have to have more lessons today, mommy?” the girl implored of her mother, tugging at her pant leg.

“Ms. Marie forgot something from earlier and has come to get it back. Come children, help mommy look.” And off Mrs. Benson went with her eyes scanning the ground and her twins in tow, mimicking her movements.

Marie found her throat closing up and that she had to swallow big gulps of air just to keep from suffocating in the dizzying atmosphere around her. She pinched herself to make sure she was awake, and was affirmed of this when she found herself drawing blood from her forearm. She walked away from the Bensons’ home, leaving the little family in there searching for something she had dropped behind her this morning, something from a time she had no memory of, a time that to the best of her knowledge she had spent sleeping.

She had lost half a day because of a nap she had intended to last for thirty minutes. She had missed Katrina’s party, she had not shown up to tutor the Benson twins. But it seemed that she had — most of what Marie had just experienced pointed to her participation in these events. She had made plans with Katrina, she had taught math to the twins, and had apparently gotten them to stop despising her.

But Marie could swear she hadn’t.

Marie shook her head, and realized with this movement that she had tears streaming down her face; impelled by anxiety, not sadness. She wiped them away — realizing too late what this would do to her day-old makeup — and tried to even her breathing, but felt, every time she lifted her head up and back to breathe deeply in, the pinprick-like pangs of a nascent migraine. She ought to get home lest she collapse in the middle of the sidewalk. She decided to take the bridge that ran over the river, the river that carved the town in two, on her way back. Surely, certainly she would have a better time breathing there.

On the bridge, Marie tried to steady herself by watching the swollen and bubbling river surge by. It didn’t make her feel dizzy; rather, it was like white noise whose white and grey pulse, reassuringly constant and steady, helped to even out her breathing, leading by interminable example. The bridge allowed only for foot traffic, of which at this lunch hour there was none. Marie was grateful for this: she felt free to be free in her movements now that she knew there were no eyes upon her.

But she wasn’t absolutely alone. A little ways down the bridge and looking over the railing as Marie had been doing was a girl. About Marie’s height.

There was something about the other girl that struck Marie to her core — she was reminded of the hours she spent in front of the mirror. Marie screwed up her eyes to get a better look at the girl through the burgeoning aching in her head. This other girl’s hair, her bare neck exposed as she leaned forward, perhaps to get a better look at the river, her arms, and finally her hands, were all motionless and statuesque, graceful even when — or because — they moved in slight measured gestures, the whispers of gestures, to brush some hair out of her face that in its balletic dance in the soft breeze had fallen as a shroud across her eyes. She was a beautiful picture of a girl looking over a bridge — a girl whose hair, neck, arms, and hands were familiar to Marie, were known by Marie as intimately and instinctively as she knew the contours and cadence of her favourite passage in her favourite book. This other girl — she was a beautiful picture of Marie.

Marie had come here to the bridge so as to be able to breathe easily, but she found, looking at this image of her, the air punched out of her. She moved slowly toward the girl, keeping her hand on the rail, for she knew she wouldn’t be able to manage herself without its support.

The girl remained as she was. Her clothes were innocuous enough, but were also vaguely familiar to Marie. Her hair swayed and danced lightly in the zephyr, the only uncontrolled aspect of her, verging on the wild. She didn’t seem to see Marie approach her.

Uncertain of how best to initiate matters, Marie lightly tapped the girl’s shoulder. She had expected for the girl to jump, to start at her touch. But the girl, in a swift and seamless movement, moved up from the rail and turned toward Marie.

“Excuse me,” Marie said, not sure where to go now that she’d begun the interaction.

“Hello,” said the girl. She smiled big, showing off perfect teeth that a part of Marie had been expecting to see because she had seen them: every time she flashed herself a smile in front of the mirror.

“What’s your name?” Marie asked.

“Marie. What’s yours?” she said, that smile still cemented across her lips — a perfect smile. Marie knew that smile — it was too friendly, too nice. This overflowing smile meant one of two things: either the girl knew who Marie was, why she had started talking to her, she possessed all the knowledge of the situation, but would still make Marie work for the information; or it meant that she knew nothing remarkable. Marie knew what this smile meant because it was her own reflected back to her in the image of this girl; it was a superficial attempt at mystery that often concealed her own social cluelessness. That it was perfect meant to Marie that it was symmetrical, in the way her mirror provided her with an even, more symmetrical image of herself.

Marie felt as though she was melting, as if she was falling and the whole of her would soon be a puddle that would eventually run down the bridge and join the river below. “Marie,” she muttered.

The other girl put forth her hand and Marie shook it. The perfect smile remained unflinching on her face, not reacting in any remarkable way to the sameness of their names or faces. If the girl possessed knowledge of what was going on, Marie reasoned, then surely her eyes would have narrowed, surely the knowledge would have tantalizingly cast a dark and heavy shadow behind her gaze. But Marie felt that the other girl’s eyes seemed vacant — flat. And so Marie surmised that the perfect smile was one of cluelessness.

“Nice to meet you,” the other girl said. “I was just staring at the water. Isn’t it wonderful?”

Definitely cluelessness, thought Marie. “Yes, I suppose it is,” Marie said. She couldn’t take her eyes off the girl. The two stared at each other for some time, and all the while Marie couldn’t escape the feeling that she was sitting in her room, watching herself in her mirror at her vanity table.

The girl, still smiling that too nice smile and not seeming to feel uncomfortable by Marie’s staring, cupped her hand above her brow and looked up at the sky. “Well,” she said finally, “I’m afraid I have to get going now. I have some appointments I need to keep. It was nice meeting you!” She thrust forth her hand again, and Marie shook it. And then the other girl, the other Marie, walked away down the bridge. Marie stood in place, swaying as if about to fall into a swoon. But she caught herself in time and began in trail of the girl, keeping her distance.

Marie didn’t know why she had begun to follow the other girl her image. Without rationalizing the act or providing herself an excuse for it, she simply fell in line a short distance from her, enough to not make herself known.

She followed her image first to a boutique. The girl who was and was not Marie seemed to have a fitting scheduled. As the slam-proof door recoiled behind the girl, and as Marie sidled up next to it, her back to the glass window, she heard, right before the door swooped shut, the salesgirl inside say, “Sorry for the wait.” Marie knew this boutique. She had always felt too intimidated by the expensiveness within to enter, but her image obviously felt no such qualms.

After some time, Marie spied her image emerge from the changing rooms sheathed in a gorgeous bright sequined shift dress, and the salesgirls fawn over her. Then she noticed something strange. The girl, Marie’s image, did not emote or speak until after the salesgirls spoke, and when she did speak, it was with the same expressions and gestures as the salesgirls, which didn’t seem to disconcert the other girls in the slightest.

But Marie didn’t linger too long on this bit of strangeness as her mind suddenly solved an earlier puzzle. The clothes that the girl was wearing, the vaguely familiar innocuous garb — it was an outfit, jeans t-shirt and a black suede coat, that Marie had seen on Katrina. And then this reminded Marie of her own much-too-extravagant outfit. But she suddenly found herself beyond feeling embarrassed about her appearance.

As the girl emerged once again from the changing room, in those clothes like Katrina’s, Marie’s eyes fell upon the wallet in the girl’s hands. It was like Marie’s wallet, the one she kept in the satchel that she had on now. And from this wallet the girl got out a credit card — issued by the bank Marie used — and paid for the dress she’d just tried on. Marie opened up her satchel. Amidst the notebooks and workbooks and textbooks she kept for her tutoring, she usually kept her wallet. But it wasn’t there, not today. She looked back up through the window and saw the salesgirl smile at Marie’s image from behind the counter, and then Marie’s image return the same smile.

Marie quickly turned around and huddled up near the shop windows next door, keeping her head down so that the girl would not see her as she left the boutique. And she didn’t — she just walked by, smiling big and staring straight ahead, as if she was balancing thick tomes on her head. Marie followed.

Marie’s image next led her to a salon, and Marie soon gathered that the girl would be there for a long while — she was apparently getting her hair cut and coloured. So Marie settled a little ways down and across the street, on a bench skirting a park. And there Marie waited. She was much too confused by and interested in her subject to do anything else — she needed to know what was going on. The girl, her image, was obviously getting ready for an event. Was it what Katrina had referred to?

But then Marie had to laugh at herself. How could this stranger, no matter her resemblance to herself and her clothes’ resemblance to Katrina’s, know of Katrina’s party? But a small voice in her head, a tiny voice that echoed and sounded as if it was coming to her from the end of a tunnel, an end miles away from her, told her that there was a connection. Told her that Katrina’s call this morning, what transpired at the Bensons’, the clothes the girl had on, the store she had gone into, and the wallet from which she paid for her new purchase — all this was connected, all this could be explained. And the explanation was Marie herself.

But the strain it put upon her to listen to the small, end-of-the-tunnel voice brought back the rumbling pinpricks of pain in her head that she had momentarily elided, and it was all she could do to concentrate on breathing and clearing her mind. Lest she enrage the pain, flare it up to a hammering and molten neon frenzy with her flurrying thoughts, trying to fit themselves together like enterprising puzzle pieces.

And so Marie breathed and waited. Hours crawled by and she wished she had a book. At least the weather is pleasant, she thought, looking up at the clear blue sky. Sundown was as yet awhile away. After three hours the girl’s hair had been coloured and set, but she didn’t emerge from the salon. Instead, she settled down in another chair in the salon and began to have her makeup done. This was an affront to Marie — she would never allow another person to put her makeup on her, for she alone knew what was best for her skin and colouring and her desires. She felt herself colouring indignant as she watched another’s hands working on this face that was very nearly hers.

Finally, another hour later, the girl came out of the salon with her shopping bag and her new hair, now a dark brown that before like Marie’s had been a dark black, and makeup. Marie waited until she was a safe distance away before she herself got up and began to follow her. She soon came to understand the route the girl was taking, but she couldn’t be sure. She didn’t want to be sure. It was probably just a coincidence.

Ambling along behind and across the street from the girl her image, down a route she could traverse blindfolded so many times before she had walked it, past buildings she had memorized, Marie refused to believe what the end-of-the-tunnel voice was screaming at her from far away. Until finally with a sinking heart she saw the girl go into the liquor store. Marie waited across the street with her fingers crossed, hoping with all her might that the girl not come out with wine and beer.

So what if she does, though, she thought. People buy beer and wine all the time, so what if she does, she kept on repeating like a magic spell. And a few minutes later the girl exited the store with a six-pack in the hand she had the bag with her new dress in, and a longer paper bag with two slender bottles inside nestled against her breast with her other arm.

Marie could hear her heart beating, could feel her chest jerking forward with every pound, as she followed the girl down streets she wished the girl wouldn’t take, making turns she wished beforehand the girl wouldn’t make.

Until finally, with bated breath, she watched the girl go up the steps to Katrina’s house and ring the doorbell and be greeted by Katrina, who squealed: “Marie! You’re on time!” And then heard the girl her image squeal in a like manner Katrina’s name.

Until she saw her disappear into Katrina Ivan’s home. Then, Marie finally allowed herself to think the fugitive thought running amok in her mind, the thought she had been ignoring throughout this whole tail job: “This girl has stolen my life.”

Marie noticed that Katrina’s backyard was aglow with her dainty new patio lights. She crept up and around the house, grateful for the long shadows nurtured by the lowering sun. She crept right up to the gate in the fence that led to the backyard and hid behind the blue spruce that grew there, so that no one arriving at Katrina’s would see her. From her vantage point she could see chairs draped in sparkling fabric and a table offering a buffet, and she could hear them all, talking and laughing, just out of sight, somewhere there in the backyard.

“You just got one six-pack?” Katrina asked, more playful than annoyed.

“Yeah, is that okay?” the voice that was like Marie’s asked, uncertain.

“Who cares, beer’s gross anyway,” said another voice, and then was followed by Katrina’s laughter, which was trailed by the laughter of Marie’s image’s.

“Thanks so much for letting me stay over at your place, by the way, and for lending me your clothes. I just hate that new paint smell,” Marie’s voice said seriously.

“It’s no problem at all,” Katrina said. “You can stay as long as you like. I’m just glad that you’ve come out of your shell. You’re actually so fun to be around. No offence!”

“None taken,” Marie’s voice said. And then Katrina laughed, and again Marie’s voice’s laughter followed only after.

“Seriously though,” Katrina went on in a lower, confidential tone. “It’s just that so many people have been interested in you. They ask me about you all the time, and I’m just so glad that you’ve started talking to them yourself now, and stopped being, well, weird. No offence!” And again Katrina laughed and Marie’s voice’s laughter fell in an echo.

Marie, from behind the blue spruce, couldn’t help but smile. “They like me,” she whispered. This girl had stolen her life, but everyone else didn’t know that — Katrina didn’t know that. And now they actually like me, Marie thought. This doesn’t have to be a bad thing, she thought. Wasn’t this her wish granted? Her wish to have her image at parties. Her wish to be liked without much labour on her part.

Marie crept back to the sidewalk and started toward home. Leaving behind her image to do all the dirty work, all that work that she hated to do but that she wanted done. She could go home and sleep, or read all those books she never before seemed to have time to read. She could be alone and stress-free, and could rest assured, for out in the world was her image earning her a good reputation.

Beautiful, resplendent thoughts swirled around in Marie’s mind, thoughts of her making a splash at all the gatherings, thoughts of everyone knowing her, liking her, even loving her. And her double, Marie had surmised, would also fulfill her tutoring duties. She would still get paid. And these thoughts pleased her, made her jubilantly happy.

And so Marie went home, floating on these happy, perfect thoughts. And she did exactly as she had wanted to do — she slept, she read all her books. She read and read and read. And when she wasn’t reading, she thought about what her image was doing in her name, that people would still be seeing her, would still be falling in love with her. Glorious scenarios flashed before her mind’s eye and she savoured them all. She was, for a few days, simply overcome with joy. She was living her perfect life — reaping the mental benefits and satisfaction of the accomplishment of all the work she hated to do, without actually doing it, and doing only what she enjoyed doing.

But then one day Marie found her fingers tapping impatiently on the edges of the book she was reading. Then the next day she found her leg bouncing as she sat cross-legged on her bed. She found that she needed to take deep breaths oftener and oftener. And then one sleepless night she finally realized what it was: she felt alone. Truly and absolutely alone.

So she decided to get out — some fresh air would be nice. But when she sat down in front of her vanity, she almost screamed with fright. She sat in front of her mirror but there was no one staring back at her as there had been before. The realization that this was the first moment since the discovery of her double that she had actually sat down in front of a mirror dawned on her as slowly as a springtime thaw. Had her reflection been gone this whole time? Was that who her image was — her literal reflection? Of course it was, she thought; it seemed to make a kind of sense.

This was the price, undoubtedly, that she had to pay for her bliss: to be without a reflection. And after this discovery her aloneness took on a more sinister gleam. She found that there was a certain heaviness to her aloneness — in the way that something deeply black seems heavy, leaden under all the colours it has absorbed — now that she was as alone as one could possibly be, without a reflection. She felt flat, one dimensional.

She monitored her bank account, noticing that her image was keeping up her rent payments — maybe it’s some kind of intuition, thought Marie. And she wasn’t too extravagant a spender, which pleased Marie. Marie wasn’t an extravagant spender. She could still do her shopping online. But she had to wonder — was her image still at Katrina’s? What could her excuse be for staying with her for so long?

A few more days passed in this deep but flat solitude, until finally her restlessness reached its apogeal point with a buzzing in her chest that refused to go away and that took all the pleasure out of sleeping, of reading. She felt profoundly bored but tried to laugh at herself about this — no one ever died of boredom, she told herself. But after her dry laughter always she felt an emptiness — she wanted to dress up, no matter what for. She wanted to perform the acts: she wanted to get into her nice clothes, she wanted to put on her makeup, acts that brought her calmness and satisfaction, acts that were an occasion for joy in her body — but only if she could watch herself performing them.

She forced herself to laugh again at her superficial concern for physical states. She was learning so much reading, expanding her mind. She ought to be happy with her intellectual state.

But still, whispered a small voice from beneath a knowledge-laden floorboard in her mind.

But ultimately, eventually, it got to be that it all wasn’t enough. What she thought was all she needed was not enough and Marie found that she absolutely, categorically could not go on breathing if she didn’t leave her apartment. So she threw caution to the wind and left without knowing for certain what she looked like — she decided she didn’t care what she looked like. She needed to breathe. She needed to feel her weight on her feet as she walked. And walk she did.

She walked and walked and walked until she found herself staring over the railing of the bridge at the waning river, dozing along, as if it had forgotten the urgency with which it had raced just a month before in July, as if it had forgotten its purpose, or just no longer cared. And there Marie greedily drank up the cooling air. The sun was setting in an enraged blaze of red and orange and pink, and Marie drank these hues, the sky up too, so greedily did she breathe.

When she had had her fill, she finally looked around. She remembered the last time that she was here and how it had then been almost empty. It was empty now too, save for one still figure down by the opposite end. Déjà vu, Marie thought. She started walking across, and the nearer she got to the end, the closer she got to the unmoving figure, the more she felt as though she knew this person. She did.

It was her graceful reflection stood gazing down at the river now become slender.

“Hey, you!” She called to her reflection.

The girl looked up and smiled that same ambiguous smile that used to be Marie’s. “Hello,” she said.

“Remember me?” Marie asked.

“No, sorry, I’m afraid I don’t. What’s your name? My name is Marie.”

“You might be beautiful, but you sure are idiotic,” Marie said in a flat voice she didn’t know she had. She felt a deep resentment for this girl. No, this ghost of a girl, this ghost of Marie probably liked by everyone more than Marie was ever liked, this mimetic shell more adored than Marie ever was and who had the privilege to not be bored, to not grow tired of sleep. She didn’t deserve this privilege, Marie decided. Marie had been grateful for her just weeks before, but now, looking at her, at her vacant smile, this doll of hers, she wanted to throw her into the river.

And why shouldn’t she? After all, it was her own reflection, her own brown-haired image. It’s not like this before me is a real person, thought Marie. It’s not like this is me, she thought, her mind’s voice become a vitriolic hiss.

And so Marie stepped up close to this girl her image and lifted her up. She was as light as Marie had expected her to be — as light and vacuous as the skin a snake sheds off. And she threw her into the river. The girl her image fell down without protest, without a scream, and she plopped into the water with a small, sharp splash, the kind of splash a small pebble might make. She bobbed along in the lazing water, until the lackadaisical waves pushed her down and the river swallowed her whole.

Marie breathed out deeply, and she felt lighter. She felt her breathing coming back to her, she felt a cool equanimity washing over her. She turned on her heels and went back to her apartment.

In her apartment, she parted her heavy curtains and let in the twilight, the soft light she used to find the most beautiful, most perfect to watch herself in the mirror in. And so Marie sat down at her vanity before her mirror and found herself looking at the landscape of her room behind her. At nothing in particular.